Aneta W. Sperber

Photos in groups

Zion National Park had existed in my mind mostly from ViewMaster slides I had seen as a child.

What a surprise!

The view from our hotel room.

The other side of the hotel.

The dining area with the most incredible breakfast buffet.

Motor scooters everywhere

Houses, gardens, shrines, rice paddies…

The government subsidizes these picturesque mountainside rice paddies. The farmers could earn more money growing soy beans.

The master weaver is the fellow on the left. In this type of traditional ikat the design is determined by pre-dyed and coded bundles of thread/yarn. (Look at the bundle on the right).

The width is determined by the size of the backstop loom, about 12″ – 14″ wide.

These are traditional patterns.

One of seven temples on the coast to protect the island.

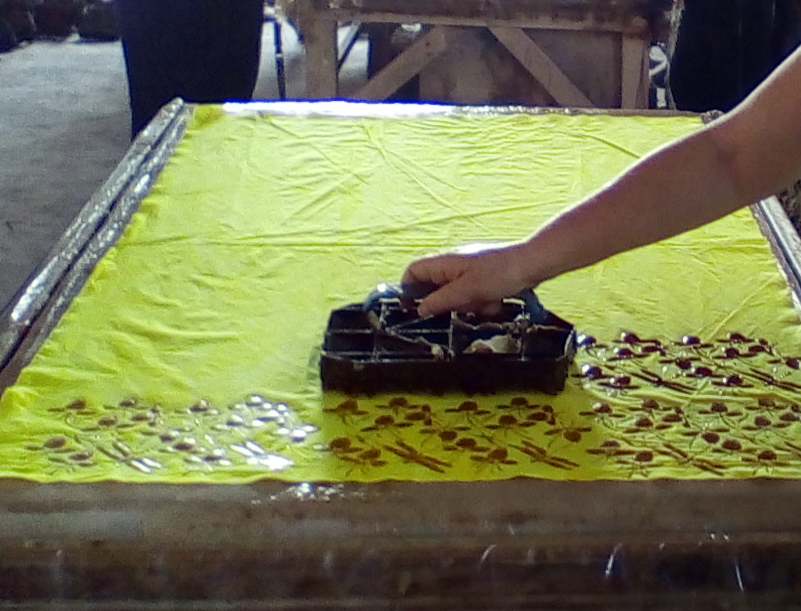

Batik production for the American, European and Asian markets takes place only during the driest parts of the year, as much of the process goes on outside and in covered, but open sheds, as above.

We had the good fortune to be able to try our hand at batik printing with hot wax.

The fabric workers can print quickly and accurately with the wax. Most of the workers are from Java and do batik printing as seasonal work, being away from home for six to eight weeks at a time.

Squirting dye for a random background.

Racks of fabric out to dry.

Stunning infinity pool

Love these double outrigger canoes with sails.

And finally, one of the many Hindu shrines you see all over Bali.

Blessings and thanks to Deb Roberts tours.

Kona Bay

Love that Kona coffee. A coffee plantation tour brings an appreciation of the labor intensive nature of this crop.

Kona Coast

On the Hilo side: Black sand beaches and turtles.

A historic canoe…

More historic canoes…

Kona Sunsets

+

I love the new graphics on the Air New Zealand planes. It’s the New Zealand Silver Fern. Some people want to change the national flag to a black and white fern flag. Very minimalist. Very cool.

Looking out the window of my bedroom at Gill’s Airbnb. Slightly suburban Wanaka.

A little Alpenglow to remind you where you are.

Arrived on a weekend and took time to walk each day around Lake Wanaka. (Skiing on weekends is something you can avoid if you are retired.)

[Rather than bore you with all my lake and mountain photos, I’m just going to stick them at the end– so if you are tired, you can leave off….]

Up to Cardrona (or Cardies as it is known locally) for a warm-up day.

This is looking toward Queenstown and Lake Wakatipu in the distance.

Then up to Treble Cone (or TC) which has the some of the great views and much more challenging skiing.

TC also has alpine parrots, the Keas. They are large, entertaining and, sadly, endangered, but recovering in numbers since my last trip.

A kea inspecting the gear.

Another view of Lake Wanaka from TC.

Sunrise on my last day of skiing for this trip. Off to Queenstown and Doubtful Sound.

xxxx

xxxx xxxx

xxxx

From the top of the Crown Range

From Cardrona looking toward The Snow Farm (the twisty road you see is the road to The Snow Farm

Love you Wanaka,

Bye, bye for now…..

And off to

It was foggy and overcast when we started out across Lake Manapouri.

Then over the mountains to the fjords.

And Doubtful Sound / Patea itself…

In the 1940s, there were a few women’s names (besides those of movie stars and singers and Eleanor Roosevelt) well-known to the general public: Sonja Henie, Babe Didrikson Zaharias, and Margaret Bourke-White. While Sonja twirled on ice, and the “Babe” smashed tennis and golf balls, Margaret Bourke-White hung out of airplanes with a camera in her hands. That kind of life, like the open cockpit airplane and the Speed Graphic, is now an artifact of American culture, but parts of the myth are still with us.

Vicki Goldberg, in Margaret Bourke-White, A Biography, did not set out to write cultural or photographic criticism, and that was probably a wise choice. The facts and fantasies of Bourke-White’s life provide Ms. Goldberg with more than enough material for this one volume. Biographers inevitably face questions of selection, and with Bourke-White as subject these problems are enormous. The gossip and rumors about Bourke-White were and are as numerous as the reports that exist in print and manuscript. All these sources, plus Bourke-While’s many contemporaries who are still alive and very talkative, no doubt made Goldberg’s task most complex.

The book straddles two biographical worlds: the mass market world of such books as Sara Davidson’s Rock Hudson, and academic biographies like Arthur and Barbara Gelb’s O’Neill or Leon Edel’s work on Henry James. While Margaret Bourke-White contains too much scholarship and detail to make it a supermarket check-out rack favorite, the intended audience is clearly a general rather than an academic one. Whether this decision was Goldberg’s or her publisher’s is not clear, but her presentation of serious scholarship in a popular format and style is often disconcerting.

Goldberg presents her materials in a narrative format. She works at making Bourke-White’s story interesting, which is odd since Margaret BourkeWhite was already a most interesting person. Goldberg holds back bits of information and reveals them later as surprises. For example, following several chapters on Bourke-White’s rise to fame and, presumably, fortune, Goldberg tells us that she was broke. The author also avoids the frequent use of dates (several times I found myself trying to figure out when something happened). The book deserves a detailed chronology and, given the complexities of BourkeWhite’s life, this is a serious omission.

In a biography one searches for reasons and explanations, but the complexities of Margaret Bourke-White’s personality are not easily solved. She was regarded by many people as an unpleasant person: arrogant, self-centered and careerist. Goldberg hypothesizes that her unconventional and idiosyncratic upbringing left her deficient in the everyday social graces. Kindness and generosity were not normal responses for her. As an adult, Bourke-White consciously taught herself to be charming and kind, if the situation demanded. Colleagues complained of the disjunction between her demanding perfectionism during the working day and her ability to tum on the charm at night.

Much of this is explained by her upbringing. Joseph White, her father, was an inventor in the printing industry, obsessed with his work. Both parents were dedicated to a life of reason and self-improvement. As a child, Margaret was expected to achieve. Goldberg tells of the very young Margaret being trained to overcome her fear of the dark. Her mother initiated an after-dark game in which she and the child would run around the outside of the house in different directions to finally meet each other. The first night her mother ran quickly around three sides of the house, meeting the tiny Margaret after she had haltingly completed only one side. Each night Margaret’s distance was lengthened until, eventually, she was happy to play outside alone after dark and, later, to remain in the house with her slightly older sister after bedtime while her parents took evening walks. Margaret’s parents felt this regimen taught independence and fearlessness, and Goldberg suggests it accounts for Bourke-White’s love of solitude and her courage. But most psychological thinking today would say such “training” is bound to leave scars. Indeed, Bourke-White’s many years in and out of analysis suggest that her upbringing of rigorous perfectionism had its negative as well as positive effects.

While few of us pass through our teens and twenties with grace and wisdom, this period was especially hard for Bourke-White. She was more awkward than the typical adolescent, and attempted to make friends with attention-getting performances such as wearing pet snakes around her neck.

Her father died while she was in college, and she married early. After two miserable years, she separated from her husband, finished college, and began her photographic career. Goldberg sees this failed early marriage as central to Margaret BourkeWhite’s need to achieve personal success and her reluctance to make longstanding personal commitments to men. But while this marriage no doubt shook Bourke-White’s self-confidence deeply, my own feeling is that her relationship to her father and mother, her unusual upbringing, and her status as a middle child are probably more accountable for these deep-seated needs.

During her early years as a professional photographer in Cleveland, Margaret Bourke-White was not yet the worldly adult we associate with the image she (and Fortune and Life magazine) had created by the mid-1930s and ’40s. She dressed for work in color coordinated suits, hats, high heels, gloves and photographic dark-cloths. Her presentation of self was completely thought out, but she knew that to earn a living she had to make good photographs as well. She over-shot extravagantly, as she continued to do throughout her career, and she began producing the work which would eventually make her a success and, later, a “star.”

During her twenties she was influenced by whatever social circles surrounded her at a given time. While photographing for the captains of industry, they were “the people that counted.” At this time also, she rarely read newspapers and didn’t follow current events at all. She was photographing the interior of a Boston bank during the evening after Black Thursday, October, 1929, and couldn’t figure out why all the staff had stayed late at the bank, thus interfering with her work.

Bourke-White does not seem a very sympathetic heroine or a genuine person until she begins to travel and gain some cultural and political sophistication. It is interesting to speculate what sort of person might have emerged had she not come under the influence of, among others, Maurice Hindus, “a foremost Russian expert, a famous, even a heroic liberal.” Would she have made her crucial first trip to Russia? Would her political education have had its leftist bias?

But a person of considerable substance and very real dedication and ability does emerge from this youthful superficiality. Her life illustrates the human potential for growth and change. She never gave up trying to improve her work, even during her twenty-year struggle with Parkinson’s syndrome. And she never gave up trying to improve herself either. But an element remains, throughout her life, of that young girl over-willing to please, trying too hard to please.

In the early fifties she was attacked by the red-baiting newspaper columnist Westbrook Pegler for her history of leftist alliances (the Film and Photo League, the League of Women Shoppers, the American Youth Congress, etc.), for her marriage to a playwright with leftist alliances, Erskine Caldwell, and for her books and films about Russia. In the midst of the HUAC frenzy it seemed as if her career might be ruined. But Margaret Bourke-White asked Life to let her cover the Korean conflict, and she produced a photo essay about a Communist guerrilla’s defection to the government forces and his reunion with his family. After the publication of the photo essay, and a year-long lecture tour which followed it, her loyalty could hardly be questioned. But what can be questioned here is the depth of her political thinking and commitments.

Whether Margaret Bourke-White became a more likable person as she matured is hard to say. People’s reactions to her continued to be strongly positive or negative throughout her life. Whole factories, from workers to executives, apparently “fell in love” with her. But others were quick to say, “everyone was her messenger boy.”

Bourke-White was also frequently criticised for behavior that would go unnoticed in a male. In her twenties, she consciously flaunted the double standard, presuming that doing a man’s work allowed her a man’s sexual prerogatives:

Early in Margaret’s career she was so successful she was rumored to be a front for a man; now [during World War II] men gave her credit solely for being female, and around Life she was soon labelled ‘the general’s mattress…: The world being what it is, some women certainly used sex for advancement, but whether they did or not many of the women who went to war as correspondents were accused of it.

While Margaret Bourke-White was hardly a conscious feminist, and while Vicki Goldberg’s presentation is not ideologically feminist, there is much illuminating material about the contradictions, difficulties and ambiguities of Bourke-White’s trek through the male dominated world of photography and news reporting. The question of how a woman ought to achieve success in a male dominated culture is one which feminists continue to debate. So, while Margaret Bourke-White’s life is fascinating and possibly instructive, there are many women for whom she could hardly be a role model.

The attitudes Bourke-White was most frequently criticized for– aggressiveness, determination, perfectionism, ruthlessness, strong sexuality– were seen as virtues in her male colleagues. Nobody demanded that men be ‘nice” and successful as well. But the mature Margaret Bourke-White seems to have been fairly immune to gossip and basically unaware of how much she was disliked around Life. For her, the work counted most.

Opting for work, and not family and personal life, is a choice few women have made on so conscious a level. While both men and women may question this choice, Bourke-White’s honesty in this area (particularly her decision not to bear children) spared her much of the painful dilemma of family versus career. (Dorothea Lange boarded out her two sons at an early age to concentrate on her photography, and there was a great deal of suffering by all three.)

For all the information concerning Bourke-White’s life that Vicki Goldberg provides, many interesting questions about that life remain unanswered. Why did America elevate Margaret Bourke-White to star status? Was it part of the Life magazine phenomenon and orchestrated by Time-Life or something deeper in the culture? What role did photography and femaleness play in her star status? Did she create the myth of the crusading photojournalist or merely bring it to its zenith? What has been the legacy from the tens of thousands of women she lectured to in the forties and fifties and the many women who emulated her?

And what about the work that Margaret Bourke-White valued above all else? Only a thorough critical assessment will guarantee her photography its place (or lack of it), in photographic history. While this sort of evaluation is beginning on the photographic work which has come out of the 1930s and 1940s, much remains to be done in analysing the area of cultural iconography– why did her images speak to the American public with such immediacy? What dreams, fantasies, and realities did her photographs fulfill?

An artist’s production must necessarily be seen in terms of his or her social reality. To separate Bourke-White’s photographs from the context of the times and approach them from a formal or aesthetic perspective would surely be a mistake. One study that comes to mind as a possible model for future work is Karin Becker Ohm’s Dorothea Lange and the Documentary Tradition. Indeed, Bourke-White’s situation is interesting for studying the questions which pertain to photographing for mass media distribution and for the questions of personal versus professional expression and ethics-questions which seem to be very much in the air given the proliferation of such films as Salvador, Under Fire, and The Year of Living Dangerously.

That Vicki Goldberg hasn’t given us all of the answers only suggests the breadth and complexity of the questions Margaret Bourke-White’s life and work raise. But, obtaining the biographical facts is always the first step, and Vicki Goldberg has done substantial ground work for future students and critics.

This review appeared in the Winter 1987 edition of Exposure magazine, Vol. 25, No.5, the Journal of the Society for Photographic Education and is copyrighted © by the SPE.

This was written for a digital literacy course in 2001. My ideas haven’t changed much since then. I am leaving out the footnotes, except to note where references exist, but if anyone would like the references, please feel free to contact me.

The end of semester student photography exhibit is a common occurrence in colleges where photography is taught (ref). On the surface, such exhibits do not look very different in 2001 than they did in 1991. The print quality is usually excellent. The prints are carefully archivally matted and framed for gallery or museum-like presentation. The sophistication and complexity of the students’ photographic vision varies widely, as is to be expected with student work. Contrary to superficial appearances, however, there are substantial differences between the photos on the student gallery walls in 2001 and those in 1991. As one student put it: “I don’t think there is a photo here which hasn’t passed through Photoshop.” What is surprising about this is that the images don’t show obvious indebtedness to Photoshop. With one or two exceptions, there is very little montage or collage among the works. They don’t look like Absolut Vodka ads. They look very much like photography has looked for a long time. There are sensitive and thoughtful portraits. There are carefully composed landscapes and cityscapes. There is some mixed media and combining of texts and images. The primary way in which the images differ from those in 1991 is that they are not traditional silver photographic prints.

These images were, in fact printed on photographic quality paper with an ink-jet printer through a computerized system. Such printers spray tiny jets of ink to create the image. If looked at with a magnifying glass, the lines of the ink-jet path across the paper can be discerned. A traditional silver photographic print, if looked at under magnification, will reveal the clumping together pattern of the grains of silver. This patterning is random, not linear. However, when viewed at a conventional viewing distance, even up close with the naked eye, these prints are indistinguishable from their darkroom, silver based predecessors. Without a discernible difference in the appearance of the product, the nature of art photography practice has changed. The potential for digital imaging to change the nature of photography has been remarked upon for some time (refs). digitization alters the nature of the photographic process. The digital file can replace the negative. Photoshop and the ink-jet printer replace the enlarger and developing trays. Will art photography evolve into a new digital art form or will it cloak itself in new technologies to make an art product similar to what has been made for the last fifty years?

Photography has always occupied a somewhat ambiguous position in the art-making community. At first it was considered too mechanical to be an artistic practice. By the time silver prints were finally gaining museum and collector acceptance in the 1970’s and 1980’s, the digitization of the medium was underway (ref). Part of what established photography as an art was the cachet attached to unique silver prints. While a photograph could never be like an original painting or drawing, the argument went, the process of photography involved the hand of the artist: at the moment of exposure and then later in the darkroom. Art photographers were encouraged to sign and number their prints, like printmakers. Photographers who relied on commercial or machine-made prints or who had assistants print their work were held in less esteem than those who did their own darkroom work. The idea of an intimate connection between the artist and the finished product was important in photography’s attempt to gentrify itself into a high art form. Even though photographs were mechanically produced, it was suggested, they still had many attributes of traditional high artworks and were, thus, collectible.

In 1998 a Dorothea Lange print sold at auction for $244,500. (ref). Entitled “Human Erosion in California 1936” this print is one of her most widely reproduced photographs and so would be easily recognized as a well-known photographic work. In addition, this particular print had an element, a portion of a child’s hand, in the lower right corner, which Lange had removed in later versions, thus making it a very unique print and contributing to the high price the Getty Museum paid.

Lange’s is an interesting example because it parallels some of the issues brought up by the digitization of the medium. Photographers have altered photographs since the invention of the medium (ref). In the late 19th Century the fact that photographs could be altered increased their acceptability as art in some circles. Artist intervention was seen as superior to strict mechanical representation. Digitization can aid this tendency toward artistic control. While Lange had to alter the negative or crop the print in some way to remove the child’s hand, the contemporary photographer can alter the digital file.

With lens and silver based photography, the starting point of the photographic image is the negative (ref). Historically, as in Lange’s case, and in thousands of others, negatives were manipulated and combined to create the works photographic artists saw in their imaginations. Digitization can intervene at several stages in the photographic process. A digital image file can be the starting point if the original image is taken with a digital camera. Or, the negative or transparency can be digitized and a file created at that point. Lastly, an already existing silver print can be scanned or photographed, resulting in a digital file.

William J. Mitchell argues that with digitization the file itself becomes the “original” work of art (ref). Mitchell goes on to suggest that digital files create artwork that is allographic, functioning something like a musical score. The work is never completed, never static, but changing with each generation or re-generation. The digital work of necessity becomes a group or team endeavor. This description is appropriate for NASA’s image files and many scientific applications, but it is not so easily applied to current art photography. Art photography continues to be a fairly solitary endeavor and not very group or team oriented. Group process may not be intrinsic to digitization. In fact, given the nature of computers as a one-on-one work environment, individualization seems at least as appropriate. Individual authorship in art photography may not diminish, as Mitchell predicts (ref), and future photographic artists may well preserve individual authorship very successfully.

When photographers make prints from individual negatives, the longevity of the negative during the repetitive process is something like printmaking. As a lithographic stone or printing plate deteriorates with use, a negative deteriorates as well. However, the negative’s degradation is more a result of handling than actual physical pressure, as in printmaking. The negative gets scratched. Dust collects; the negative has to be cleaned. It gets scratched again. Photographic prints made earlier in a negative’s life will likely be higher quality than those made later. Mitchell is right to point out that this just doesn’t happen with a digital file (ref). Even though digital image files can be ephemeral and highly mutable (ref), they have the potential to be much more stable than negatives or printing plates. What this means is that digital prints can theoretically be generated at any time without regard to intrinsic longevity.

In practical terms, there may be a caveat: computer systems and software change. Today’s file from Photoshop 6.0 may not open in later versions of the program. However, this potential for reproducibility is what really makes the May 2001 student photo exhibit different. If all those prints on exhibit were to deteriorate or were destroyed, one hundred years from now, if someone came across the CD-ROM, the prints could all be produced again, exactly as the students had intended them to look, provided the “antique” software and appropriate printers could be re-activated.

This is heart warming in some ways. All that artwork is preserved from the ravages of time and air and light and moisture. If a print in a particular exhibit or collection gets damaged, just print another one. But, consider the havoc this can create in the already fragile photographic art market. If artworks are easily replaceable, where is their value as a collectible?

First, there is no doubt that silver prints, signed and made by art photographers, will appreciate dramatically as the implications of digitization begin to sink in to the consciousness of the collecting public. This is already the case with the big names, but anything silver-based will be likely to appreciate. There is a brisk market in vernacular photography on eBay, and this will only accelerate as attic troves of silver prints become more and more scarce.

Color photography presents other problems. A large percentage of the vernacular color photographic prints of the 1950’s, 1960’s and 1970’s were unstable, and these have already degraded badly. On the art production end, photographers were aware of these permanence problems, and many attempted to use the most stable color processes for their work. These more stable color prints, along with Kodachrome slides, which have always been well-known for their longevity, will probably rise in value along with black and white prints. An excellent recent example of the increasing attention to Kodachrome slides is the Cushman Archive at Indiana University (ref). While the decision here has been to share these wonderful Kodachrome images on the WWW, their implicit value is recognized by the university library’s decision to create the archive and so valorize them.

But museums and libraries that readily collect black and white silver prints and Kodachrome slides may well be suspicious about collecting digital prints. Current research indicates that high quality ink-jet prints are very stable and permanent, (ref). Longevity, historically a bugaboo with collecting color photographic work, can no longer be seen as a serious issue, and digitization has created the potential to make infinite multiple artworks from the same source.

Right now it may take some time for the collecting public to notice that there are fundamental differences between digital and traditional silver photographic prints. After all, the digital and photographic print can look superficially identical. Will digital artists find ways to make their work attractive to collectors and museums? The notion of signed, limited editions (always kind of silly with photography) will probably continue. Some artists may advocate and follow through on destroying their digital files at the end of an edition of digital prints. Collectors may initially shun digital prints the way the painting and print buying public originally shunned silver photographs, but eventually, just as photography became accepted, digital art photography will be accepted, displayed and collected. A.D. Coleman also suggests that a new category of artwork is emerging which he calls “computer art” (ref). Such works, whether they exist on the WWW, on CD- ROM’s, or in printed versions may in embody the true potential of digital media in the visual arts. Like photographs at the birth of the medium one hundred and fifty years ago these digital artworks will now be the poor cousins in the art establishment and occupy the ambiguous position photography occupied for so long.